The Myth of the Coup Contagion

Naunihal Singh, Journal of Democracy, october 2022

Naunihal Singh is associate professor in the Department of National Security Affairs at the U.S. Naval War College and the author of Seizing Power: The Strategic Logic of Military Coups (2014). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Naval War College, Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

The recent spate of coups and coup attempts—six successful and three failed attempts in the span of twelve months—is not an indication that coup activity will return to the high levels seen during the Cold War. There is no evidence of a contagious wave; what we are seeing is simply the coincidence of already coup-prone countries (mainly in Africa) having coup attempts in the same period. These attempts were also not driven by increased insurgent activity or by western training of these militaries. However, this flurry of coup activity has revealed that post–Cold War norms against coups have eroded and will likely continue to get weaker, making a return to post-Cold war levels of coup activity unlikely.

In the early hours of 23 January 2022, shots rang out in military barracks across Burkina Faso’s capital, Ouagadougou, and in two other cities, signaling a coup attempt. Over the course of the day, young protesters fed up with the government’s failure to stop jihadist attacks in the country poured into the streets and clashed with security forces as the gunfire drew ever closer to the home of President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré, who had been reelected to a second term in 2020. The next day, Lieutenant-Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba announced that the military was deposing Kaboré and taking over. The French-trained Damiba had served in an elite guard under autocrat Blaise Compaoré, Burkina Faso’s longtime leader who had himself come to power via coup in 1987 and lost power via coup in 2014.

This was just one of five successful military coups d’état in Africa between February 2021 and February 2022—in Chad, Mali, Guinea, Sudan, and Burkina Faso—plus one in Burma. During the same period, there were also failed putsches in Niger, Sudan, and Guinea-Bissau. These six successful coups marked a sizeable jump in military interventions over the average of two successful coups a year between 2015 and 2020.1 Here, I define a coup attempt as an explicit action involving some portion of the state military, police, or security forces that is undertaken with the intent to overthrow the government. This encompasses not only the obvious coup attempts but also situations where there were mass protests against the incumbent, as long as the state-security apparatus was part of the removal of the government—for example, by threatening to remove the president if he does not agree to step down. The revolutions in Egypt (2011) and Sudan (2019) are therefore classified both as coups and as popular revolutions.

In a September 2021 address to the UN General Assembly, Secretary-General Antonio Guterres stated that “military coups are back.” A month later, just after the October 25 coup in Sudan, he warned of an “epidemic of coups d’état.” And at a summit of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) days after the January coup in Burkina Faso, Ghanaian president and ECOWAS chair Nana Akufo-Addo lamented that a “contagion” of coups could potentially “devastate” the region. But Guterres and Akufo-Addo are wrong. The recent spate of coups d’état is not the product of a contagion; nor is it, as some contend, an outgrowth of insurgent violence or the insidious effect of Western military training.2 Diagnosing them as such misses the real root causes and, therefore, the opportunity to better prevent coups in the future.

There is no contagion of coups

With so many coups happening in such a short span of time—often in neighboring or nearby countries—it is easy to imagine the dominoes falling. Yet what has been happening over the past several years is not a shocking outbreak of putsches in stable countries, with each attempted overthrow informing and inspiring the next. All these countries had long and often recent histories of coups d’état and military rule or meddling in politics. The eight states that saw coup attempts between February 2021 and 2022 are among the countries with the most attempts since 1950. Potential coupmakers therefore had no need to look beyond their borders for proof that coups could be successful or for guidance on how to pull them off.

These cases also show little evidence of the mechanisms of contagion, such as emulation and learning, although it is difficult to tell from the outside. The lack of contagion in these cases is consistent with what I was told in interviews with officers who had plotted and attempted coups in West Africa. While they were aware of coup attempts in other countries, they did not consider such events relevant to their own calculations, which were focused squarely on domestic factors, with a heavy emphasis on military concerns. Statistical analysis also supports the claim that coups do not spread by contagion. The most extensive study of the topic to date used a technique called extreme-bounds analysis that examined nearly 1.2 million models in an attempt to avoid spurious inferences. This study found no evidence that coups spread by contagion, although more mass-driven political events, such as protests and strikes, do.3

Coups are not the product of insurgent violence

The countries of the Sahel—but also elsewhere in the world—have for years been facing steadily rising insurgent violence. Terrorist incidents in the Sahel soared in 2021, rising from 1,180 to 2,005 violent events; the number of fatalities doubled from 2020; and there are currently some 2.4 million people displaced in the region.4 National militaries have struggled to deal with the challenges posed by insurgent groups operating in their countries and have often found themselves outmatched. In Burkina Faso, grievances over insufficient training and resources for counterinsurgency efforts were at the center of the January 2022 coup. A similar dynamic was at play a decade ago in Mali, when junior officers, angry over insufficient support for fighting the civil war, ended two decades of democracy in that country.

Yet, of the 2021–22 coups, only Burkina Faso’s clearly fits the bill of soldiers overthrowing their government because of grievances related to counterinsurgency efforts. Neither Guinea nor Guinea-Bissau is contending with insurgencies or terrorism. And although there are serious internal conflicts in Burma, Chad, Mali, and Sudan, the military men who mounted those coups were already part of the power structure—a structure they aimed to preserve, not to overturn, with their power grabs.

If insurgent violence were truly driving the coups, then there would have been numerous attempts in the Sahel in 2015, when insurgent violence was at its highest—claiming at least ten-thousand lives, more than twice as many as during the recent peak in 2020.5 Yet, between 2015 and 2020, there was just a single attempted coup in the region: a failed putsch in Burkina Faso, which had nothing to do with insurgent violence and everything to do with military infighting. Although the stresses of insurgency may degrade the quality of democracy and decrease popular support for the incumbent, harm civil-military relations, and increase frustration between military officers and those in power, these factors explain neither the timing nor the number of countries recently experiencing coups.6

Western military training is not causing coups—despite how it looks

Most recent coup attempts have either been carried out by military men who were trained or educated in the United States or have taken place in countries where the U.S. military had a significant presence. The most striking example is the coup in Guinea. On 5 September 2021, a group of officers from Guinea’s elite special forces, led by their commander, the 41-year-old former French legionnaire Colonel Mamady Doumbouya, left in the middle of a months-long Green Beret training in the town of Forécariah. The coupmakers drove four hours to the capital, Conakry, where they battled their way into the presidential palace, took 83-year-old President Alpha Condé captive, and overthrew his government.7

Mali’s interim president, Colonel Assimi Go¦ta, who seized power in 2020 and again in 2021, had extensive U.S. military training in both Africa and the United States, including during U.S. Africa Command’s annual special-operations exercise on the continent (known as Flintlock). The leader of Mali’s 2012 coup, Captain Amadou Haya Sanogo, learned English in a U.S. military program in Texas and completed infantry and intelligence training in Georgia and Arizona, respectively.8 Damiba, the most recent Burkinabé coup leader, had participated in multiple U.S.-led exercises and trainings in Burkina Faso and Senegal, while Lieutenant-Colonel Yacouba Isaac Zida, leader of the 2014 coup in Burkina Faso, had attended counterterrorism and military-intelligence training courses conducted by the U.S. military in both the United States and Botswana.9

The U.S. military has close institutional relationships with the militaries of Niger and Chad, but does not appear to have trained the leaders of the coups there. Niger hosts the largest U.S. military contingent in the region. At the time of the failed coup in March 2021, days before the president-elect was to take office, roughly eight-hundred U.S. military personnel were stationed there.10 Chad’s army, meanwhile, is the lynch-pin in Western counterterror operations in the Sahel and works closely with both the U.S. and French militaries. The coup in Chad followed the April 2021 death of President Idriss Déby (in power since 1990) from battlefield injuries. Chad’s constitution called for the head of the National Assembly to become interim president, but the Transitional Military Council assumed power and installed Déby’s son, General Mahamat Déby, instead.

Despite all this, studies that have examined the entire range of U.S. military training of foreign militaries have found no statistical linkage between the amount of training given and the increased likelihood of a coup attempt.11 U.S. Africa Command does not track how often officers whom it has trained try to overthrow their governments. But given that between 1999 and 2016, thirty-four U.S. military training programs taught 2.4 million soldiers abroad, it is hardly surprising that some of the recent putschists had participated in them.12

In addition, foreign military training varies considerably in subject, duration, location, and purpose. There are brief trainings lasting only days that are focused on a single technical subject and longer courses that last weeks, months, or even almost an entire year. Some are conducted in a soldier’s home country by visiting instructors, others take place in third countries in the region, and sometimes foreign military personnel study in the United States. High-ranking officers, in particular, often attend programs run by foreign militaries or go abroad for military training—not just in the United States, but also in other countries including China, Canada, England, France, and Russia.

The Real Roots of Coup Activity

If neither contagion, nor insurgent violence, nor international training is to blame for the recent wave of coups, then what is? Three key structural factors made these countries particularly vulnerable to coup attempts: a recent history of successful coups, low economic development, and regimes that are neither highly democratic nor highly authoritarian.13

The coup trap

Past successful coups in a country increase its risk of suffering future coup attempts. As noted above, the eight countries that experienced coup attempts between February 2021 and 2022 were no strangers to the coup d’état. To name just three examples, elected governments in Mali fell to coups in 2012, 2021, and 2022; the transitional government in Sudan that was overthrown in 2021 had come to power after popular uprisings and military intervention toppled the previous autocratic regime in 2019; and the 2022 coup in Burkina Faso followed the 2014 coup that ousted a dictator already weakened by his own political miscalculations and massive popular protests.

Moreover, all but Chad and Burma had seen at least one other coup attempt in the ten years prior. Sudan has experienced three coup attempts since 2019 alone, for a total of sixteen since independence (1956)—the third-highest number of any country in the world since 1950. Including the most recent events, Burkina Faso and Guinea-Bissau each have seen nine coup attempts and Mali, eight.

Low economic development

Coup attempts are most common in countries with low levels of economic development. The eight countries that experienced coup attempts between February 2021 and 2022 were among the poorest in the world, ranking in the bottom fifth of world economies (by GDP per capita), according to the World Bank. They also ranked low on other measures of development such as infant mortality.

Regime type

Fully consolidated democracies and highly authoritarian regimes with well-developed repressive apparatuses are less likely to experience coup attempts than countries that fall somewhere in between, sometimes called anocratic or hybrid regimes. Most of the states that have suffered recent coup attempts would be considered either hybrid regimes or fledgling democracies that lack consolidated institutions and norms. Seven of the nine coup attempts occurred in countries with (at least nominally) elected governments. The two exceptions were Mali and Sudan, both of which had unelected transitional governments in 2021 that had been put in place after the overthrow of their previous regimes. The fairness of the elections in the other six countries varied considerably, from very fair in Burkina Faso to a total sham in Chad. Freedom House characterized all eight countries that experienced coup attempts as Partly Free or Not Free.

The Rise and Fall of Anti-Coup Norms

During the Cold War, the UN Security Council never addressed the issue of coups d’état.14 And fewer than 30 percent of all coups from 1975 to 1989 received any international condemnation from the West at all, even when taking into account the statements made by all Western governments and liberal multilateral organizations including the United Nations and IMF.15 But late in the Cold War, an international norm against coups began to develop as a byproduct of the burgeoning prodemocratic norms taking root around the same time.

In 1985, the U.S. Congress passed the Foreign Assistance and Related Programs Appropriations Act, prohibiting foreign aid from going to El Salvador in the event that the president of the country was removed by a military coup. Congress widened the scope of the law the following year to stop the flow of broad categories of economic and security aid to any country whose leader had been deposed in a coup. This provision, known as Section 7008, has been a part of the State Department’s annual appropriations bill ever since.16

By 1990, a majority of coups were condemned by at least one Western government or associated liberal multilateral organization, and every coup that took place between 2005 and 2009 was.17 When financial and diplomatic penalties accompanied such censure, the costs of coupmaking shot up significantly, especially in developing economies undergoing structural adjustment. These countries were often desperate for capital, so losing access to financial aid from the West and the IMF could be a very big deal indeed.

The United Nations began to embrace the norm against coups after the 1991 military coup in Haiti, which the UN General Assembly condemned. In 1994, the Security Council adopted a resolution authorizing the UN Mission in Haiti to use “all necessary means” to remove the military junta and restore the legitimate government. This pressure helped to return the deposed president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, to power.

Along with Western nations and liberal multilateral organizations, two regional organizations in the most coup-prone regions also embraced anti-coup norms: the Organization of American States (OAS) and the African Union (AU). Both the OAS and the AU adopted measures enabling the suspension of member states after a coup. The OAS’s 1991 Santiago Commitment to Democracy and 1992 Protocol of Washington (which went into effect in 1997) called for the suspension of any country whose democratically elected government had been overthrown by force. The Inter-American Democratic Charter, signed in 2001, specified how the OAS should proceed in the event of an interruption of democracy in a member state.

The AU’s predecessor, the Organisation of African Unity (1962–2002), was never particularly committed to prodemocratic norms, and instead emphasized sovereignty and noninterference. The Constitutive Act of the African Union (2000), however, prohibits unconstitutional changes of government in its member states, as does the 2007 African Charter on Democracy, Elections, and Governance, which went into effect in 2012.18 Not all regional organizations embraced this norm equally, however. Both the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) prioritize sovereignty and have members that oppose prodemocratic norms.

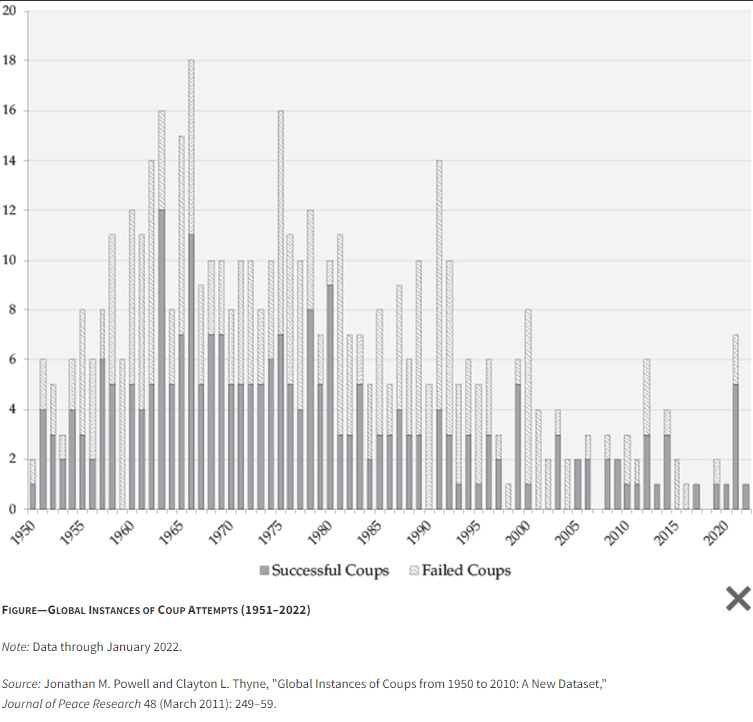

Since the end of the Cold War, coup activity has decreased dramatically. During the Cold War, there were, on average, nine coup attempts a year, and not a single year passed without at least one attempt somewhere in the world. But in the last three decades, there have been only 3.7 coup attempts a year on average, less than half the earlier level. Formerly coup-prone regions, such as Latin America, the Middle East, and Asia, now go multiyear stretches without a single attempt. Even Africa, which still tops the rest of the world in coup activity, has seen a 20 percent drop in coup attempts.

What accounts for this change? Although multiple factors are surely at play, statistical analysis has found that the threat of international sanctions has contributed to the post–Cold War decrease in coup activity, especially when criticism comes from a major power, trading partner, or ally.19 It is also worth noting that coupmakers today tend to explain or justify their actions with language that seems to be responsive to anti-coup norms. In fact, in the post–Cold War era, successful putschists have been three times more likely to claim that their military intervention was not, in actuality, a coup; twice as likely to justify their actions in terms of democratic values; and 45 percent more likely to say that they were taking power only temporarily.20 All this suggests that the rise of anti-coup norms, more broadly, has helped to curb coupmaking globally.

For some time, however, anti-coup norms have been eroding, weakening their deterrent effect. There are two key reasons for this: inconsistent enforcement and the rise of regimes that do not share this norm. It is not easy for any country or multilateral organization to prioritize punishing (and hence discouraging) coups over competing political and security concerns. This is true even for those countries and bodies that pioneered and promoted anti-coup norms in the first place. The United States, for example, does not always cut off financial aid after a coup. The legislation requiring it to do so applies only to coups that unseat a “duly elected” leader. Thus there was no automatic cessation of aid to Niger after the 2010 coup or Zimbabwe after the 2017 overthrow of Robert Mugabe, although in both cases aid was stopped for other reasons. Countries where coups were accompanied by popular protests, such as Burkina Faso in 2014, have also been exempted from the automatic imposition of sanctions on the grounds that the event was a “popular uprising” and not a coup.

When coups topple governments in strategically important countries, the U.S. State Department can decline to formally declare those changes in government to be coups. This happened in Egypt in 2013, Algeria in 2019, and Chad in 2021. In the case of Egypt, Congress went so far as to insert new language into the 2014 appropriations bill making it clear that funds could still go to Egypt. In fact, in the past decade, only Fiji, Guinea-Bissau, Madagascar, Mali, and Thailand have been cut off as a result of the anti-coup restrictions in the Foreign Aid Appropriations Bill. In addition, while the State Department did not classify events in Honduras in 2009 and Niger in 2010 as automatically invoking sanction under the law (Honduras was categorized as not a “military coup,” and the military intervention in Niger was not considered a coup because the president had overstayed his original constitutional term), it did voluntarily suspend aid to these countries in a manner consistent with the law.21

Section 7008 was written narrowly to apply to cases where the military acts largely alone and takes power by overthrowing a duly elected president. It does not require that the State Department make a determination as to whether a military intervention is a coup. This is something that Congress could easily change but so far has chosen not to, most likely because of the priority placed on maintaining security assistance.

The United Nations has also been both inconsistent and weak in responding to coups. Despite the UN’s strong response to the coups in Haiti in 1991 and Sierra Leone in 1997, the Security Council has since been silent on the vast majority of coups, including those in Pakistan (1999), Egypt (2013), and Thailand (2006 and 2014). The Security Council rarely issues formal resolutions condemning military takeovers. When it does, its censure usually targets coups in countries with little strategic importance to its permanent members, such as the 2012 coup in Guinea-Bissau.22 While the Security Council’s press releases have been more critical of coups than have its resolutions, it almost never imposes major sanctions after a coup.23 Although the Security Council is the UN body that is best equipped to apply penalties enforcing the anti-coup norm, China and Russia do not accept this norm, the United States is ambivalent about strong international institutions, and all members at certain times might simply prefer to prioritize other concerns over creating an effective deterrent to future coups.

The Power of Peer Pressure?

Some regional bodies vigorously condemn coups but are still generally unwilling to do much else in response—for example, to impose sanctions or restore the previous government by force. The AU has suspended all but two member states whose governments have fallen to coups since 2010, the exceptions being Zimbabwe in 2017 and Chad in 2021. Of the countries that experienced coups between February 2021 and 2022, Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali, and Sudan were suspended—a record number of member suspensions in a single year. It is worth noting that Chad dodged suspension largely on specious grounds related to internal insecurity in the country.24 Yet Burkina Faso and Mali also face a significant transnational insurgent threat and were still suspended. This discrepancy shows that even organizations that are generally consistent about suspending members will still defer to political pressure when it comes to strategically important countries. The bigger problem for the African Union, however, is that membership suspension alone is not truly a significant penalty for most members (membership confers mainly diplomatic benefits, and does not come with either economic or security goods), and therefore seems neither to deter coupmakers nor to force them to restore democracy quickly.

Other regional organizations, including ASEAN, refuse to penalize their members for coups d’état. ASEAN abides by the principles of consensus and nonintervention. Moreover, China, while not a member, is the biggest power in the neighborhood and a major trading partner for most ASEAN members. Not only did ASEAN not impose any penalties after coups in Thailand (2014) and Burma (2021), but the body failed even to criticize the coupmakers for what they had done. Needless to say, sanctions—diplomatic and economic—were off the table. Similarly, the GCC neither censured nor sanctioned the 2021 coup in Sudan.

Even when countries do face sanctions for coups, they can now cushion the blow because they have other options for patrons and allies. In the first two decades after the Cold War, by contrast, most developing countries relied almost exclusively on the United States and other Western countries and organizations. But today, the military junta in Burma, for example, can offset U.S., EU, U.K., and Canadian sanctions with Chinese financial and diplomatic support. Chinese foreign policy opposes sanctions, which it sees as an intrusion into a country’s internal affairs. Thus Beijing has supported the junta even though China had also maintained close relations with the Aung San Suu Kyi–led National League for Democracy administration that the military deposed, and even though Beijing has reason to worry about the possible destabilization of Burma under the junta. Similarly, after a 2006 military coup in Fiji, Chinese aid to Fiji rose from US$23 million to $161 million.25

Although Beijing’s opposition to prodemocratic norms is the most consequential given the size and weight of the Chinese economy, it is not the only country that coupmakers can turn to. After Egypt’s military overthrew President Mohamed Morsi in 2013, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) rushed to pledge $12 billion to support Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s junta in the first week after the coup.26 While the United States, IMF, and World Bank have all paused economic assistance to Sudan after the 2021 coup, the UAE has offered the military government $6 billion in long-term investments and a $300 million deposit into Sudan’s central bank.27

Russia has proved itself another powerful potential backer, although more in the realm of security than financing. France had once been Mali’s primary external security partner, but relations between France and Mali soured during the nine years of France’s counterinsurgency campaign in Mali, and became appreciably worse as a result of the military coup. In 2021, France announced that it would scale back its presence in Mali. Whereas in the past the Malian junta might have had to compromise with the French to maintain significant levels of foreign security support, Mali’s junta was instead able to invite in the Wagner Group, a Kremlin-linked private military firm, whose mercenaries began arriving at the end of that year. At the beginning of 2022, Mali expelled France’s ambassador and in May withdrew from its defense accords with the former colonial power.

The combination of reluctant (or silent) condemnation of coups by prodemocratic organizations and the increase of potential support from countries that do not embrace anti-coup norms is making it easier for juntas to evade significant punishment—thereby reducing the deterrent effect on would-be coupmakers. This does not mean that we will start seeing coup attempts in countries where they had previously been unlikely. But it may remove some of the factors that discourage coup plotters—particularly in countries experiencing a contested transition, where military actors are actively considering pushing civilian partners out of the government.

Given the enduring domestic factors that make countries vulnerable to coups and an evolving international order that can shield coup leaders from punishment and inure them to inducements to restore the old order, coup activity is not likely to fall to the low levels seen in the post–Cold War era. Rather, the current increase in coup activity may be long-lasting and may continue to grow.

Countering Coups

Although Western governments want to promote and support the spread and consolidation of democracies around the world, they too often place economic and security goals first. As a result, the West will continue to penalize juntas inconsistently and only in countries deemed strategically unimportant. Sanctions will be levied against countries such as Fiji but not Honduras, Mali but not Chad, and never against Egypt or Pakistan. Applying penalties sporadically will weaken their deterrent effect: Why would an aspiring coup leader not expect at least a chance of being spared any negative consequences associated with seizing power?

As the geostrategic rivalry between the West and China and Russia intensifies, democracy promotion risks becoming less of a priority for the West. This will have two serious consequences. First, repairing anti-coup norms will be put permanently on the backburner. And second, Western countries may choose not to impose sanctions for coups that remove hostile elected governments and replace them with pro-Western military juntas. At the same time, Russia and China will have stronger incentives to continue undermining anti-coup norms. Russia is now returning to Africa, and while it has far less to offer now than it did during the Cold War, the Kremlin has clear incentives to build a broader portfolio of diplomatic and economic partnerships, especially given the sanctions imposed on it since its invasion of Ukraine. The Kremlin, therefore, will probably try to undercut sanctions against the juntas that recently grabbed power.

Beijing has made it clear that it considers unilateral sanctions to be illegitimate and believes that penalizing countries that have military regimes is an interference in their internal affairs. If the United States and Europe delink their economies from China’s and their relationships with Beijing become more confrontational, Beijing may respond by more aggressively courting countries that the West has actively shunned. The promise of Chinese support—even if it is not enough to fully replace lost support from Western countries or from suspended IMF or World Bank loans—might substantially undercut the deterrent effect of any anti-coup sanctions that are applied.

For now, regional organizations such as the OAS, AU, and ECOWAS may continue to oppose coups, but are unlikely to do more to enforce anti-coup norms than what they have been doing already. Worse still, they may begin to do even less. These bodies, after all, have only limited ability to punish military juntas, and not one of them has the leverage that big donor countries possess. All three can threaten diplomatic penalties, but the suspension of membership in a regional body can carry only so much weight as a deterrent.

The failure of ECOWAS sanctions against Mali may be instructive in this regard. ECOWAS imposed a series of harsh sanctions in response to Mali’s 2021 coup (its second in less than a year) and Go¦ta’s proposal to delay the return to democracy for five years. In addition to suspending Mali’s membership in the organization, Malian government assets held in the Central Bank of West African States were frozen, land and air travel within member states were prohibited, and a significant amount of trade with ECOWAS countries was banned.28 Similar sanctions that were imposed after Mali’s 2019 coup were estimated to have reduced imports by as much as 30 percent, enough to cause significant economic disruption.29

But rather than offer to significantly shorten the timetable for democratization, Go¦ta’s junta dug in, gaining assurances from neighboring Guinea (another ECOWAS member led by a military junta) and Mauritania (a non-ECOWAS member) that they would not enforce the trade embargo. At the same time, that embargo hurt other ECOWAS members, including Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal, raising the cost of meat amid rising global inflation. The junta managed to convince Malians that both ECOWAS and France were to blame for their problems; it was the sanctions, not the military takeover, that were harming people’s livelihoods. This narrative inevitably damaged ECOWAS’s standing in Mali, and in the end it was ECOWAS that blinked. After a July 5 meeting with Mali’s leaders, ECOWAS gave up on sanctions without obtaining the desired concessions from the junta.30 After failing so drastically to enforce significant and sustained penalties on Mali’s junta, ECOWAS leaders will probably not mount a similar response again; their mild responses to the coups in Guinea (sanctions against the junta alone) and Burkina Faso (a mere warning) indicate as much.

So what does all this mean? Are coups “back,” as Antonio Guterres warned? The answer is not straightforward. Coup activity is increasing, but not everywhere. Latin America, once a hotbed of military intervention, has seen a dramatic drop in coup activity in recent decades. There has not been a successful coup attempt in Argentina, where attempted power grabs once abounded, since 1976. Twenty years ago, the presidency of Argentina changed hands four times in two weeks without even the hint of a coup.

Africa is a different story. The seven countries that recently experienced coups will be even more vulnerable to future coups. Democratic decline across the region will expand the number of hybrid regimes with weak institutions. And years of a global pandemic followed by Russia’s war on Ukraine, which is having worldwide ramifications, are not making poor countries any richer. All these conditions make the region ripe for coups. Outside of Africa, Burma, Thailand, and Pakistan are facing similar circumstances; each has suffered successful coups with no significant sanctions as a result.

International norms against coups have eroded and are likely to become weaker still. Penalties against coupmaking are also weak and inconsistently applied. When Western countries fail to act against coups out of fears of disrupting security relationships, they appear hypocritical, preaching the virtues of democracy but placing a low value on democracy-promoting actions in practice. When Western countries do sanction military governments, Beijing, Moscow, and other authoritarian powers are willing to step into the breach, thus further reducing the deterrent impact of any anti-coup action. All these factors have contributed to the most serious democratic slump in decades.

In the end, there is no substitute for clear and consistent implementation of prodemocratic and anti-coup norms, without loophole or exception. This can be inconvenient in the best of circumstances; sometimes it can be very costly for competing strategic priorities. In the long term, however, steadfast support for these norms will lead to a more democratic and peaceful world. Anything less guarantees that governments will continue to be overthrown by the militaries that are meant to serve them.

Notes

1. All references to the number of coups between 1950 and the present are derived from the updated version of the Powell and Thyne coup dataset: Jonathan M. Powell and Clayton L. Thyne, “Global Instances of Coups from 1950 to 2010: A New Dataset,” Journal of Peace Research 48 (March 2011): 249–59. The definition of a coup in this dataset is slightly different from the one provided in this essay.

2. See, for example, “ECOWAS Chairman Says ‘Contagious’ Mali Coup Has Set a Dangerous Trend,” France24, 3 February 2022, www.france24.com/en/africa/20220203-west-african-leaders-hold-summit-after-wave-of-coups-bring-turmoil-to-region; Beverly Ochieng, “Burkina Faso Coup: Why Soldiers Have Overthrown President Kaboré,” BBC, 25 January 2022, www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-60112043; Nick Turse, “Another U.S.-Trained Soldier Stages a Coup in West Africa,” The Intercept, 26 January 2022, https://theintercept.com/2022/01/26/burkina-faso-coup-us-military.

3. Michael K. Miller, Michael Joseph, and Dorothy Ohl, “Are Coups Really Contagious? An Extreme Bounds Analysis of Political Diffusion,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 62 (February 2018): 410–41.

4. Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS), “Surge in Militant Islamist Violence in the Sahel Dominates Africa’s Fight Against Extremists,” 24 January 2022, https://africacenter.org/spotlight/mig2022-01-surge-militant-islamist-violence-sahel-dominates-africa-fight-extremists.

5. ACSS, “Surge in Militant Islamist Violence.”

6. While there is some scholarship that demonstrates a statistical relationship between civil wars and coup attempts in general, it does not apply well to the dynamics observed in these particular coup attempts. Curtis Bell and Jun Koga Sudduth, “The Causes and Outcomes of Coup During Civil War,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 61 (August 2017): 1432–55.

7. Declan Walsh and Eric Schmitt, “U.S. Forces Were Training the Guinean Soldiers Who Took Off to Stage a Coup,” New York Times, 10 September 2021.

8. Lee J.M. Seymour and Theodore McLauchlin, “Does US Military Training Incubate Coups in Africa? The Jury Is Still Out,” The Conversation, 28 September 2020, http://theconversation.com/does-us-military-training-incubate-coups-in-africa-the-jury-is-stillout-146800.

9. Stephanie Savell, “U.S. Security Assistance to Burkina Faso Laid the Groundwork for a Coup,” Foreign Policy, 3 February 2022, http://foreignpolicy.com/2022/02/03/burkina-faso-coup-us-security-assistance-terrorism-military.

10. U.S. White House, “Letter to the Speaker of the House and President Pro Tempore of the Senate Regarding the War Powers Report,” 8 June 2021, www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/06/08/letter-to-the-speaker-of-the-house-andpresident-pro-tempore-of-the-senate-regarding-the-war-powers-report.

11. While a highly influential early study by Savage and Caverly (2017) found a relationship between training in two major U.S. foreign-military education programs and the likelihood of a coup in a country, later research that examined a broader set of U.S. military training programs does not support that conclusion. See Jesse Dillon Savage and Jonathan D. Caverley, “When Human Capital Threatens the Capitol: Foreign Aid in the Form of Military Training and Coups,” Journal of Peace Research 54 (July 2017): 542–57; Stephen Watts et al., Building Security in Africa: An Evaluation of U.S. Security Sector Assistance in Africa from the Cold War to the Present (Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, 2018); Theodore McLauchlin, Lee J.M. Seymour, and Simon Pierre Boulanger Martel, “Tracking the Rise of United States Foreign Military Training: IMTAD-USA, a New Dataset and Research Agenda,” Journal of Peace Research 59 (March 2022): 286–96.

12. Nick Turse, “The Military Isn’t Tracking US-Trained Officers in Africa,” Responsible Statecraft blog, 30 March 2022, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2022/03/30/us-military-isnt-tracking-the-officers-it-trains-in-africa; Seymour and McLauchlin, “Does US Military Training Incubate Coups in Africa?”

13. Naunihal Singh, Seizing Power: The Strategic Logic of Military Coups (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014).

14. Richard Gowan and Ashish Pradhan, “Why the UN Security Council Stumbles in Responding to Coups,” International Crisis Group, 24 January 2022, www.crisisgroup.org/global/why-un-security-council-stumbles-responding-coups.

15. Taku Yukawa, Kaoru Hidaka, and Kaori Kushima, “Coups and Framing: How Do Militaries Justify the Illegal Seizure of Power?” Democratization 27 (July 2020): 816–35.

16. Alexis Arieff, Marian L. Lawson, and Susan G. Chesser, “Coup-Related Restrictions in U.S. Foreign Aid Appropriations,” Congressional Research Service, 24 February 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11267/11.

17. Yukawa, Hidaka, and Kushima, “Coups and Framing.”

18. Oisín Tansey, “The Fading of the Anti-Coup Norm,” Journal of Democracy 28 (January 2017): 144–56.

19. Jonathan Powell, Trace Lasley, and Rebecca Schiel, “Combating Coups d’Etat in Africa, 1950–2014,” Studies in Comparative International Development 51 (December 2016): 482–502. Clayton Thyne et al., “Even Generals Need Friends: How Domestic and International Reactions to Coups Influence Regime Survival,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 62 (August 2018): 1406–32.

20. Yukawa, Hidaka, and Kushima, “Coups and Framing.”

21. Arieff, Lawson, and Chesser, “Coup-Related Restrictions in U.S. Foreign Aid Appropriations.”

22. Oisín Tansey, “Lowest Common Denominator Norm Institutionalization: The Anti-Coup Norm at the United Nations,” Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations 24 (April–June 2018): 287–305.

23. Tansey, “The Fading of the Anti-Coup Norm.”

24. Paul-Simon Handy and Félicité Djilo, “AU Balancing Act on Chad’s Coup Sets a Disturbing Precedent,” ISS Africa, 2 June 2021, https://issafrica.org/iss-today/au-balancing-act-on-chads-coup-sets-a-disturbing-precedent.

25. Jian Yang, “China in Fiji: Displacing Traditional Players?,” in The Pacific Islands in China’s Grand Strategy: Small States, Big Games (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 75–88.

26. Tansey, “The Fading of the Anti-Coup Norm.”

27. Nafisa Eltahir, “Exclusive UAE to Build Red Sea Port in Sudan in $6 Billion Investment Package,” Reuters, 21 June 2022, sec. Middle East, www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/exclusive-uae-build-red-sea-port-sudan-6-billion-investment-package-2022-06-20.

28. Agence France-Presse, “Mali’s Junta Breaks Off from Defense Accords with France,” VOA, 2 May 2022, www.voanews.com/a/mali-s-junta-breaks-off-from-defenseaccords-with-france-/6554711.html.

29. Tiemoko Diallo, “West African Bloc May Lift Mali Sanctions Soon, Says Envoy,” Reuters, 23 September 2020, www.reuters.com/article/us-mali-security-idUSKCN26E2XR.

30. This is not to say that the Malian junta offered nothing. They passed a new electoral law, made arrangements for an election authority, and assured ECOWAS that elections would be held in 2024.

Contribua para a continuidade de Dagobah apoiando Augusto de Franco.