Uma taxonomia das falácias

Franklin Veaux, Franklin Veaux’s Journal, 23 de abril de 2012.

Tradução livre (sem revisão) de Renato Jannuzzi Cecchettini (em 28/12/2021)

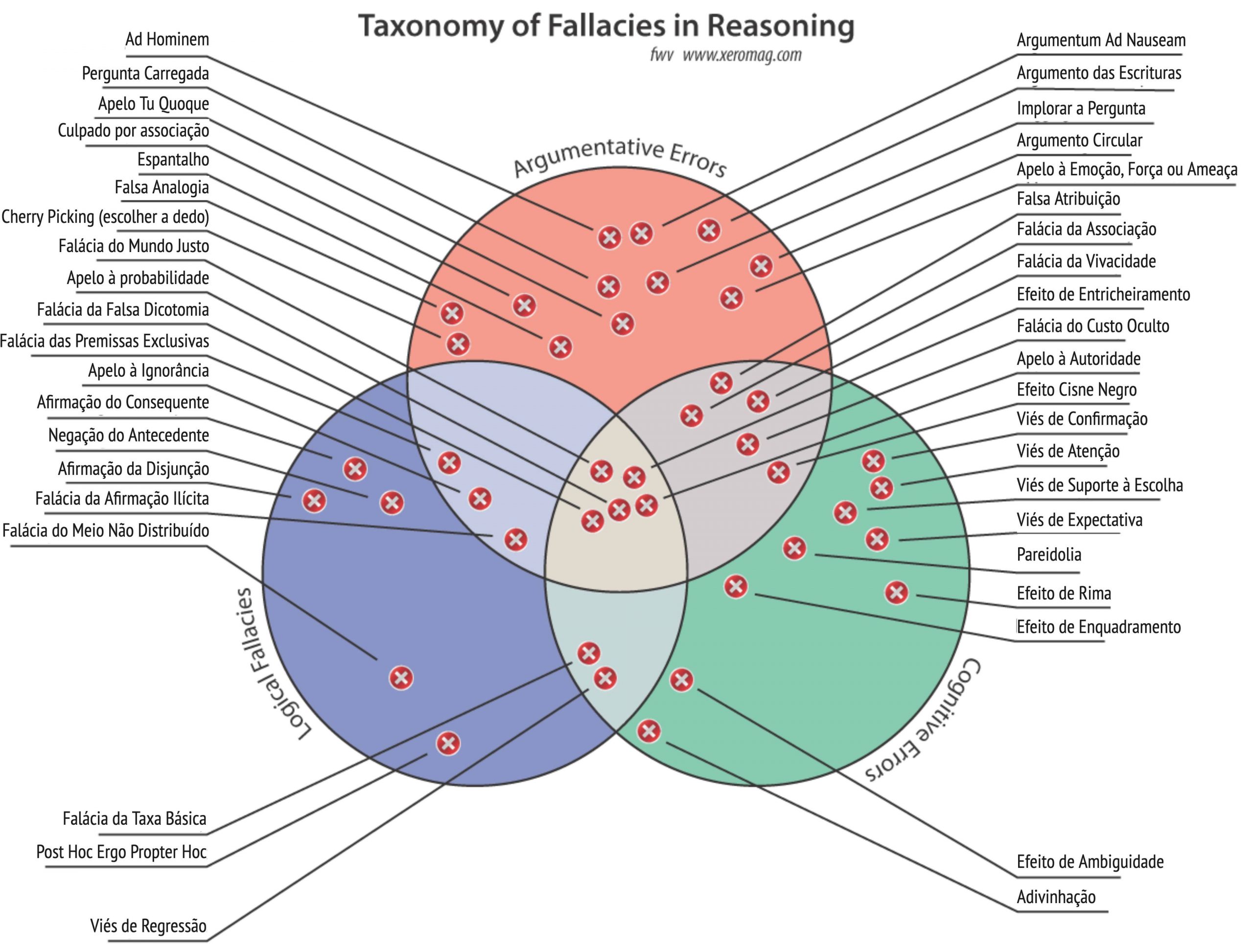

Como qualquer pessoa que lê este blog regularmente sabe, sou um grande fã de diagramas de Venn. Ultimamente, tenho pensado muito sobre erros cognitivos, erros de raciocínio e falácias lógicas, por razões que apenas coincidentemente acontecem, isso acontece no mesmo tempo das primárias políticas.

De qualquer forma, reuni uma taxonomia simples de falácias comuns. Quer dizer, uma lista exaustiva de falácias. Compilar tal lista seria certamente atentar contra a paciência dos mais santos. No entanto, pretende-se mostrar a sobreposição de falácias argumentativas (argumentos que, por sua natureza e estrutura, são inválidos), falácias lógicas (erros de raciocínio lógico) e vieses cognitivos (erros da razão humana e do nosso processo de cognição geral).

Uma visão geral rápida e suja das várias falácias está no gráfico abaixo:

Ad Homenim: Um ataque pessoal à pessoa que está apresentando um argumento. “Você é um idiota! Só um idiota pensaria algo assim.”

Pergunta carregada (Loaded Question): um argumento que pressupõe sua própria resposta, pressupõe uma de suas próprias premissas, ou pressupõe alguma suposição na forma como é formulada. “Você já parou de bater em sua esposa?”

Apelo Tu Quoque: Tu quoque significa literalmente “você também”. É uma discussão que tenta desacreditar um argumento não com base em quão válido o argumento é, mas com base em alguma inconsistência percebida ou hipocrisia na pessoa que o faz. “Você diz que uma dieta vegetariana é mais saudável do que uma dieta rica em carnes vermelhas, mas eu vi você comer bife, então você claramente nem mesmo acredita no seu próprio argumento. Por que eu deveria?”

Culpado por Associação (Guilt By Association): também chamada de “falácia de associação”, é um argumento que afirma que existe uma associação entre duas coisas, o que significa que eles pertencem à mesma classe. Pode ser feito para desacreditar um argumento atacando a pessoa que o faz (“Bob diz que devemos não comer carne; a Radical Animal Liberation Terror Front apóia o argumento de Bob. Portanto, o argumento de Bob é inválido”) ou para criar uma associação para apoiar uma afirmação que não pode ser suportada por seus próprios méritos (“John é negro; fui assaltado por um negro; portanto, John não é confiável”).

Espantalho (Straw Man): Uma técnica argumentativa que ignora o real argumento de uma pessoa e, em vez disso, refuta um argumento muito mais fraco que parece relacionado ao argumento original de alguma forma (“Bob acha que devemos tratar os animais com respeito; a ideia de que os animais são exatamente iguais às pessoas é claramente um absurdo”).

Falsa Analogia: Uma técnica argumentativa que cria uma analogia entre duas coisas não relacionadas e, em seguida, usa a analogia para tentar fazer uma afirmação (“O governo é como uma empresa. Uma vez que a função de uma empresa é ganhar dinheiro, o governo não deve promulgar políticas que não geram receita”).

Cherry Picking (Escolhido a Dedo): uma tática que apresenta apenas informações que apoiam um argumento, mesmo que outras informações não o suportem, ou as informações apresentadas são mostradas fora do contexto para fazer com que pareçam apoiar o argumento (“A vacinação causa autismo. Andrew Wakefield publicou um artigo que mostra que a vacinação causa autismo, então deve ser (verdade)” – embora centenas de outros experimentos e artigos publicados não mostrem nenhuma conexão e o artigo de Wakefield tenha sido considerado uma fraude e o autor se retratado).

Falácia do Mundo Justo: a tendência de acreditar que o mundo deve ser justo, de modo que quando coisas ruins acontecem, as pessoas a quem acontecem devem ter feito algo errado e merecido, e quando coisas boas acontecem, a pessoa com quem eles aconteceram deve ter merecido. Isso é tanto um viés cognitivo (tendemos a ver o mundo desta forma em um nível emocional, mesmo se conscientemente soubermos que não) e uma tática argumentativa (para, por exemplo, um advogado de defesa defendendo um estuprador pode dizer que a vítima estava fazendo algo errado por sair à noite com vestido curto, e portanto, trouxe o ataque sobre si mesma). Parte do que torna isso tão cognitivamente poderoso é a ilusão de controle que ela traz; quando nós acreditamos que coisas ruins acontecem porque as pessoas com quem aconteceram estavam fazendo algo errado, podemos nos assegurar de que, contanto que não façamos nada de errado, essas coisas não acontecerão conosco.

Apelo à Probabilidade: uma tática argumentativa em que uma pessoa alega que porque algo pode acontecer, isso significa que vai acontecer. Eficaz em grande parte porque o cérebro humano é extremamente pobre em compreensão da probabilidade. “Posso ganhar na loteria; portanto, eu simplesmente preciso jogar com frequência e tenho certeza de ganhar, o que resolverá todo o meu problema financeiro.”

Falácia da Falsa Dicotomia: Também chamada de “falácia da falsa escolha” ou a “falácia do falso dilema”, esta é uma falácia argumentativa que configura a falsa premissa de que existem apenas duas possibilidades que precisam ser consideradas quando de fato existem mais possibilidades. “Ou cortamos gastos com educação ou acumulamos um enorme déficit orçamentário. Não queremos um déficit, então temos que cortar os gastos com educação”.

Falácia das Premissas Exclusivas: também chamada de “falácia do negativo ilícito”, esta é uma falácia lógica e argumentativa que começa com duas premissas negativas e tenta tirar delas uma conclusão afirmativa: “Democratas não-registrados a votar são independentes; Independentes não-registrados votam em uma primária fechada; Portanto, Democratas não-registrados votaram em uma primária fechada.”

Apelo à Ignorância: Também chamado de “argumento da ignorância”, este é um dispositivo retórico que afirma que um argumento deve ser verdadeiro porque não foi provado ser falso, ou que deve ser falso porque não foi provado ser verdadeiro (“Não podemos provar que existe vida no universo a não ser em nosso próprio planeta, então deve ser verdade que a vida existe apenas na Terra”). Muitos argumentos para a existência de um deus ou de forças sobrenaturais assumem esta forma.

Afirmação do Consequente: Uma falácia lógica que afirma que uma premissa deve ser verdadeira se uma consequência da premissa for verdadeira. Formalmente, leva a forma “Se P, então Q; Q; portanto, P ”(por exemplo:“Todos os cães têm pulgas; este animal tem pulgas; portanto, este animal é um cão”).

Negação do Antecedente: Uma falácia lógica que afirma que alguma premissa não é verdadeira porque um consequente não é verdadeiro. Formalmente, leva à forma “Se P, então Q; não P; portanto, não Q.” Por exemplo: “Se houver um incêndio nesta sala, deve haver oxigênio no ar. Não há fogo nesta sala. Portanto, não há oxigênio no ar.”

Afirmação da Disjunção: às vezes chamada de “falácia da falsa exclusão”, esta falácia lógica afirma que se uma coisa ou outra pode ser verdade, e o primeiro é verdadeiro, isso deve significar que o segundo é falso (das duas, uma). Por exemplo: “Bob pode ser um policial ou Bob pode ser um mentiroso. Bob é um policial; portanto, Bob não é um mentiroso.” A falácia afirma que exatamente um ou outro deve ser verdadeiro; ignora o fato de que ambos podem ser verdadeiros ou ambos podem ser falsos. (Observe que na lógica booleana, há um operador chamado de “exclusivo ou” ou “XOR”, que significa que apenas uma coisa ou outra, mas não ambas, poderia ser verdade; isso não está relacionado à falácia lógica de afirmar a disjunção.)

Falácia da Afirmação Ilícita: este é o outro lado da falácia das premissas exclusivas. Ela afirma uma conseqüência negativa a partir de duas afirmações. “Todos os verdadeiros americanos são patriotas; alguns patriotas estão dispostos a lutar por seu país; portanto, deve haver alguns verdadeiros americanos que não estão dispostos a lutar por seu país.”

Falácia do Meio Não Distribuído: uma falácia lógica que afirma que os X são Y; algo é um Y; portanto, algo é um X. Por exemplo, “Todos os batistas do sul são cristãos; Bob é um cristão; portanto, Bob é um batista do Sul.” Esta falácia ignora o fato de que “todos os X são Y” não implica que todo Y deve ser X.

Falácia da Taxa Básica: uma falácia lógica que envolve a falha na aplicação geral de informações sobre alguma probabilidade estatística (a “taxa básica” de algo sendo verdadeiro) para um exemplo ou caso específico. Por exemplo, dada a informação que diz que o HIV é três vezes mais prevalente entre homossexuais do que heterossexuais, e dada a informação de que os homossexuais constituem 10% da população, a maioria das pessoas que ouvem “Bob tem HIV” concluirá erroneamente que é bastante provável que Bob seja gay, porque eles vão considerar apenas o fato de que os gays são mais propensos a terem HIV, mas não consideram a “taxa básica” que os gays compõem uma porcentagem relativamente pequena da população. Essa falácia é extremamente fácil de fazer devido ao fato de que o cérebro humano é muito pobre em compreensão de estatísticas e probabilidade.

Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc: em latim significa “Após o fato, portanto, por causa do fato.” Às vezes chamado de “falácia de causa falsa”, é uma falácia lógica que afirma que se uma coisa acontecer e então algo mais acontecer, a primeira coisa fez com que a segunda coisa acontecesse (“Meu filho foi vacinado contra o sarampo; meu filho foi diagnosticado com autismo; portanto, a vacina causou o autismo”). Nossos cérebros são altamente sintonizados para encontrar padrões e buscar causalidade, até o ponto em que frequentemente a vemos mesmo quando não existe.

Viés de Regressão: esta é uma falácia intimamente relacionada ao post hoc, ergo propter hoc falácia porque atribui uma causa falsa a um evento. Neste caso em particular coisas que normalmente flutuam estatisticamente tendem à uma média; uma pessoa pode ver a causa nessa regressão à média, mesmo onde nenhuma existe. Por exemplo: “Bob teve uma sequência incrível de sucessos quando ele estava jogando basquete. Em seguida, ele apareceu na capa da Sports Illustrated. Depois disso, seu desempenho foi mais medíocre. Portanto, aparecendo na capa da revista deve ter feito com que ele tivesse um desempenho ruim.” Uma vez que mesmo bons atletas geralmente retornam ao seu desempenho médio após desempenho particularmente excepcional (ou particularmente ruim), aparecer na capa da revista provavelmente não terá relação com o desempenho do atleta regredindo para a linha de base normal desse atleta.

Argumentum Ad Nauseam: Uma estratégia retórica em que uma pessoa continua a repetir algo como verdadeiro continuamente, mesmo depois disso ter sido provado ser falso. Alguns comentaristas de rádio são particularmente propensos a fazer isso: “Sandra Fluke quer que os contribuintes paguem pela contracepção. Ela argumenta que é responsabilidade do contribuinte pagar por sua contracepção. Sandra Fluke acredita que a contracepção deveria ser paga pelo contribuinte.”

Argumento das Escrituras: Um argumento que afirma que se algum elemento em uma fonte sendo citada é verdadeiro, então toda a fonte deve ser verdadeira. Esta falácia não se aplica exclusivamente a escrituras sagradas ou bíblicas, embora muitas vezes seja usada em argumentos religiosos.

Implorar a Pergunta (Begging the Question): Semelhante à falácia da pergunta carregada, este é um argumento em que algum argumento assume sua própria premissa. Formalmente, é um argumento em que a conclusão que o argumento afirma demonstrar faz parte da premissa do argumento. “Nós sabemos que Deus existe porque vemos na natureza exemplos do desígnio de Deus.” A premissa deste argumento assume que a natureza é projetada por Deus, que é a conclusão que o argumento pretende sustentar.

Argumento Circular: esta tática argumentativa está relacionada a implorar a pergunta, mas um pouco diferente no sentido de que usa um argumento para reivindicar provar outro, então usa a verdade do segundo argumento para apoiar o primeiro. Muitas pessoas consideram o raciocínio circular a mesma coisa que Implorar a Pergunta, mas eles são ligeiramente diferentes: na falácia de implorar onde a questão contém a conclusão de um argumento como uma de suas premissas, enquanto o raciocínio circular usa o argumento A para provar o argumento B, e então, tendo provado que o argumento B é verdadeiro, usa o argumento B para provar o argumento A.

Apelo à Emoção, Força ou Ameaça: uma tática argumentativa em que, em vez de fornecer evidências para mostrar que um argumento é correto, a pessoa que faz o argumento tenta manipular as emoções do público (“Você deve considerar Bob culpado deste assassinato. Se você não disser que ele é culpado, então você deixará um assassino perigoso livre para atacar suas crianças”).

Falsa Atribuição: um argumento em que uma pessoa tenta sustentar uma posição soa mais crível, atribuindo-a a um conhecido ou fonte respeitada, ou usando uma fonte bem conhecida e respeitada com comentários fora do contexto, de modo a criar uma falsa impressão de que fonte apoia o argumento. Como disse Abraham Lincoln, mais de 90% das citações usadas para apoiar argumentos na Internet não são confiáveis!

Falácia da Associação: uma forma generalizada de falácia de culpado por associação, uma falácia de associação é qualquer argumento que torne qualquer afirmação de que alguma semelhança irrelevante entre duas coisas demonstra que essas duas coisas estão relacionadas. “Bob é bom em palavras cruzadas. Bob também gosta de trocadilhos. Portanto, podemos esperar que Jane, que também é boa em palavras cruzadas, deva gostar de trocadilhos também.” Porque nossos cérebros são eficientes em categorizar as coisas em grupos, muitas vezes somos propensos a acreditar que categorizações são válidas mesmo quando não o são.

Falácia da Vivacidade (Vividness Fallacy): também chamada de “falácia da vivacidade enganosa”, é a tendência de acreditar que eventos especialmente vívidos, dramáticos ou excepcionais são eventos mais relevantes ou mais estatisticamente comuns do que realmente são e dão atenção especial ou atribuem um peso especial a tais eventos vívidos e dramáticos ao avaliar argumentos. Uma estratégia retórica comum é usar exemplos vívidos para criar a impressão de que algo é comum quando não é: “Em Nova Jersey, um veterano do Vietnã foi agredido em um bar. Em Vermont, um veterinário da guerra do Iraque foi assaltado com uma faca. Os cidadãos americanos odeiam veteranos!”. Isto é eficaz por causa de um viés cognitivo chamada de “heurística de disponibilidade”, o que nos leva a julgar mal a importância estatística de um evento, se pudermos pensar em exemplos deste evento.

Efeito de Entrincheiramento (Entrenchment Effect): também chamado de “efeito de tiro pela culatra”, é uma tendência de pessoas que, quando apresentadas a evidências que refutam algo que elas acham que é verdade, muitas vezes tendem a formar um apego maior à ideia de que deve ser verdade. Eu escrevi um ensaio sobre enquadramento e entrincheiramento aqui.

Falácia do Custo Oculto (Sunk Cost Fallacy): Um erro de raciocínio ou argumento que sustenta que se um certo investimento foi feito em algum curso de ação, então a coisa certa a fazer é continuar nesse curso de ação para não desperdiçar esse investimento, mesmo diante das evidências que mostram que esse curso de ação provavelmente não terá sucesso. Em retórica, as pessoas costumam usar argumentos para apoiar uma posição tênue com base no custo irrecuperável ao invés do mérito da posição. “Devemos continuar a investir neste projeto de armas, embora os engenheiros digam que é improvável que funcione porque já gastamos bilhões de dólares nisso, e você não quer esse dinheiro para ser desperdiçado, não é?” Esses argumentos geralmente são bem-sucedidos porque as pessoas criam apegos emocionais a uma posição em que sentem que fizeram algum investimento que está completamente desconectado do valor da própria posição.

Apelo à Autoridade: Também conhecido como o argumento da autoridade, é um argumento que afirma que algo deve ser verdadeiro com base no que uma pessoa que geralmente é respeitada ou reverenciada diz que é verdade, ao invés da força dos argumentos que apoiam isso. Como animais sociais, nós tendemos a dar peso desproporcional aos argumentos que vêm de fontes que gostamos, respeitamos ou admiramos.

Efeito Cisne Negro: também chamado de falácia do cisne negro, é a tendência de descontar ou desacreditar informações ou evidências que caem fora da gama particular de experiência ou conhecimento de uma pessoa. Pode assumir a forma de “Nunca vi um exemplo de X; portanto, X não existe”; ou pode assumir uma forma mais sutil (chamada de “falácia de confirmação”) em que uma afirmação é considerada verdadeira porque nenhum contra-exemplo foi demonstrado (“Eu acredito que cisnes negros não existem. Aqui está um cisne. É branco. Aqui está outro cisne. Também é branco. Eu examinei milhões de cisnes, e todos eles são brancos; com todos esses exemplos que apoiam a ideia de que cisnes negros não existem, esta declaração deve ser muito confiável!”).

Viés de Confirmação: a tendência de perceber, lembrar e/ou dar peso particular para coisas que se encaixam em nossas crenças pré-existentes; e não perceber, não lembrar e/ou não dar peso a nada que contradiga nossas crenças pré-existentes. Quanto mais acreditamos em algo, mais notamos e mais claramente nos lembramos das coisas que apoiam essa crença, e menos notamos coisas que contradizem essa crença. Isto é um dos mais poderosos de todos os vieses cognitivos.

Viés de Atenção: um viés cognitivo em que tendemos a prestar atenção especial às coisas que têm algum tipo de ressonância emocional ou cognitiva e ignorar dados que são relevantes, mas que não têm essa ressonância. Por exemplo, as pessoas podem tomar decisões com base em informações que as fazem sentir medo, mas ignoram informações que não provocam uma resposta emocional; uma pessoa que acredita que “muçulmanos são terroristas” pode se tornar hiperconsciente do comportamento ameaçador percebido de alguém que ele sabe ser muçulmano, especialmente quando essa percepção reforça sua crença de que os muçulmanos são terroristas e ignoram as evidências que indicam que essa pessoa não é uma ameaça.

Viés de Suporte à Escolha (Choice Supportive Bias): a tendência ao lembrar uma escolha ou explicando porque alguém fez uma escolha, acreditar que a escolha é melhor do que realmente era, ou acreditar que outras opções são piores do que elas realmente eram. Por exemplo, ao escolher uma das duas ofertas de emprego, uma pessoa pode descrever o trabalho que ela escolheu como sendo claramente superior ao trabalho que ela não aceitou, mesmo quando ambas as ofertas de emprego eram essencialmente idênticas.

Viés de Expectativa: também às vezes chamado de “viés do experimentador”, é a tendência das pessoas de colocarem mais confiança ou credibilidade em resultados experimentais que confirmam suas expectativas do que em resultados que não correspondem às expectativas. Também se mostra na tendência das pessoas em aceitar sem questionamento a evidência que é oferecida que tende a apoiar suas ideias, e para questionar, desafiar, duvidar ou descartar evidências que contradizem suas crenças ou expectativas.

Pareidolia: a tendência de ver padrões, como rostos ou palavras, em estímulos aleatórios. Os exemplos incluem pessoas que afirmam ver o rosto de Jesus em um pedaço de torrada ou quem ouve mensagens satânicas em discos de música reproduzidos em sentido contrário.

Efeito de Rima: a tendência das pessoas de achar mais críveis declarações que rimam do que aquelas que não rimam. Sim, isso é real, um viés cognitivo demonstrado. “Se a luva não couber, você deve absolver!” (“If the glove don’t fit, you must acquit!”)

Efeito de Enquadramento (Framing Effect): a tendência de avaliar evidências ou fazer escolhas

de forma diferente dependendo de como está enquadrado. Eu escrevi um ensaio sobre enquadramento e entrincheiramento aqui.

Efeito de Ambiguidade: a tendência das pessoas de escolherem um curso de ação em que eles sabem a exata probabilidade de um resultado positivo ao longo de um curso de ação em que a exata probabilidade não é conhecida, mesmo se a probabilidade de um resultado positivo é geralmente algo em torno do mesmo, ou se o possível resultado positivo é melhor. Há uma demonstração interativa deste efeito aqui.

Adivinhação (Fortunetelling): a tendência de fazer previsões sobre o resultado de uma escolha e, em seguida, assumir que a previsão é verdadeira e usar a previsão como uma premissa em argumentos para apoiar essa escolha

Nota desta edição. Esta tradução pode ser melhorada. Confira com o original abaixo (e ajude, se puder):

A Taxonomy of Fallacies

As anyone who reads this blog regularly knows, I’m a big fan of Venn diagrams. Lately, I’ve been thinking quite a lot about cognitive errors, errors in reasoning, and logical fallacies, for reasons which only coincidentally happen to coincide with the political primary season–far be it from me that the one might be in any way whatsoever connected to the other.

Anyway, I’ve put together a simple taxonomy of common fallacies. This is not, of course, an exhaustive list of fallacies; compiling such a list would surely try the patience of the most saintly. It is, however, intended to show the overlap of argumentative fallacies (arguments which by their nature and structure are invalid), logical fallacies (errors in logical reasoning), and cognitive biases (errors of human reason and our general cognitive processes).

As usual, you can clicky on the picture to embiggen it.

A quick and dirty overview of the various fallacies on this chart:

Ad Homenim: A personal attack on the person making an argument. “You’re such a moron! Only an idiot would think something like that.”

Loaded Question: An argument which presupposes its own answer, presupposes one of its own premises, or presupposes some unsupported assumption in the way it’s phrased. `”Have you stopped beating your wife yet?”

Appeal Tu Quoque: Tu quoque literally means “you also.” It’s an argument that attempts to discredit an argument not on the basis of how valid the argument is, but on the basis of some perceived inconsistency or hypocrisy in the person making it. “You say that a vegetarian diet is more healthy than a diet that is rich in red meats, but I’ve seen you eat steak so you clearly don’t even believe your own argument. Why should I?”

Guilt By Association: Also called the “association fallacy,” this is an argument which asserts that an association exists between two things which means they belong to the same class. It can be made to discredit an argument by attacking the person making it (“Bob says that we should not eat meat; the Radical Animal Liberation Terror Front supports Bob’s argument; therefore, Bob’s argument is invalid”) or to create an association to support an assertion that can not be supported on its own merits (“John is black; I was mugged by a black person; therefore, John can not be trusted”).

Straw Man: An argumentative technique that ignores a person’s actual argument and instead rebuts a much weaker argument that seems related to the original argument in some way (“Bob thinks we should treat animals with respect; the idea that animals are exactly the same as people is clearly nonsense”).

False Analogy: An argumentative technique that creates an analogy between two unrelated things and then uses the analogy to attempt to make an assertion (“The government is like a business. Since the function of a business is to make money, the government should not enact policies that do not generate revenue”).

Cherry Picking: A tactic which presents only information that supports an argument, even if other information doesn’t support it, or even the information which is presented is shown out of context to make it appear to support the argument (“Vaccination causes autism. Andrew Wakefield published one paper that shows vaccination causes autism, so it must be so–even though hundreds of other experiments and published papers show no connection, and Wakefield’s paper was determined to be fraud and retracted”).

Just World Fallacy: The tendency to believe that the world must be just, so that when bad things happen the people who they happen to must have done something wrong to bring them about, and when good things happen, the person who they happened to must have earned them. It’s both a cognitive bias (we tend to see the world this way on an emotional level even if we consciously know better) and an argumentative tactic (for example, a defense attorney defending a rapist might say that the victim was doing something wrong by being out at night in a short dress, and therefore brought the attack upon herself). Part of what makes this so cognitively powerful is the illusion of control it brings about; when we believe that bad things happen because the people they happened to were doing something wrong, we can reassure ourselves that as long as we don’t do anything wrong, those things won’t happen to us.

Appeal to Probability: An argumentative tactic in which a person argues that because something could happen, that means it will happen. Effective in large part because the human brain is remarkably poor at understanding probability. “I might win the lottery; therefore, I simply need to play often enough and I am sure to win, which will solve all my money problems.”

Fallacy of False Dichotomy: Also called the “fallacy of false choice” or the “fallacy of false dilemma,” this is an argumentative fallacy that sets up the false premise that there are only two possibilities which need to be considered when in fact there are more. “Either we cut spending on education or we rack up a huge budget deficit. We don’t want a deficit, so we have to cut spending on education.”

Fallacy of Exclusive Premises: Also called the “fallacy of illicit negative,” this is a logical and argumentative fallacy that starts with two negative premises and attempts to draw an affirmative conclusion: “No registered Democrats are registered Independents. No registered Independents vote in a closed primary. Therefore, no registered Democrats vote in a closed primary.”

Appeal to Ignorance: Also called the “argument from ignorance,” this is a rhetorical device which asserts that an argument must be true because it hasn’t been proven to be false, or that it must be false because it hasn’t been proven to be true (“we can’t prove that there is life in the universe other than on our own planet, so it must be true that life exists only on earth”). Many arguments for the existence of a god or of supernatural forces take this form.

Affirming the Consequent: A logical fallacy which asserts that a premise must be true if a consequence of the premise is true. Formally, it takes the form “If P, then Q; Q; therefore P” (for example, “All dogs have fleas; this animal has fleas; therefore, this animal is a dog”).

Denying the Antecedent: A logical fallacy that asserts that some premise is not true because a consequent is not true. Formally, it takes the form “If P, then Q; not P; therefore, not Q.” For example: “If there is a fire in this room, there must be oxygen in the air. There is no fire in this room. Therefore, there is no oxygen in the air.”

Affirming the Disjunct: Sometimes called the “fallacy of false exclusion,” this logical fallacy asserts that if one thing or another thing might be true, and the first one is true, that must mean the second one is false. For example, “Bob could be a police officer or Bob could be a liar. Bob is a police officer; therefore, Bob is not a liar.” The fallacy asserts that exactly one or the other must be true; it ignores the fact that they might both be true or they might both be false. (Note that in Boolean logic, there is an operator called “exclusive or” or “XOR” which does mean that either one thing or the other, but not both, could be true; this is not related to the logical fallacy of affirming the disjunct.)

Fallacy of Illicit Affirmative: This is the flip side of the fallacy of exclusive premises. It affirms a negative consequent from two affirmative statements. “All true Americans are patriots; some patriots are willing to fight for their country; therefore, there must be some true Americans who aren’t willing to fight for their country.”

Fallacy of Undistributed Middle: A logical fallacy that asserts that X are Y; something is a Y; therefore, something is an X. For example, “All Southern Baptists are Christians; Bob is a Christian; therefore, Bob is a Southern Baptist.” This fallacy ignores the fact that “all X are Y” does not imply that all Y must be X.

Base Rate Fallacy: A logical fallacy that involves failing to apply general information about some statistical probability (the “base rate” of something being true) to a specific example or case. For example, given information which says that HIV is three times more prevalent among homosexuals than heterosexuals, and given the information that homosexuals make up 10% of the population, most people who are told “Bob has HIV” will erroneously conclude that it is quite likely that Bob is gay, because they will consider only the fact that gays are more likely to have HIV but will not consider the “base rate” that gays make up a relatively small percentage of the population. This fallacy is extremely easy to make because of the fact that the human brain is so poor at understanding statistics and probability.

Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc: This is Latin for “After the fact, therefore, because of the fact.” Sometimes called the “fallacy of false cause,” it’s a logical fallacy which asserts that if one thing happens and then something else happens, the first thing caused the second thing to happen (“My child had a measles vaccine; my child was diagnosed with autism; therefore, the vaccine caused the autism”). Our brains are highly tuned to find patterns and to seek causation, to the point where we often see it even when it does not exist.

Regression Bias: This is a fallacy that’s closely related to the post hoc, ergo propter hoc fallacy in that it ascribes a false cause to an event. In this particular case, things which normally fluctuate statistically tend to return to a mean; a person may see cause in that regression to the mean even where none exist. For example, “Bob had an amazing string of successes when he was playing basketball. Then he appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated. Afterward, his performance was more mediocre. Therefore, appearing on the cover of the magazine must have caused him to perform more poorly.” Since even good athletes will generally return to their baseline after particularly exceptional (or particularly poor) performance, appearing on the cover of the magazine is likely to be unconnected with the athlete’s performance regressing to that athlete’s normal baseline.

Argumentum Ad Nauseam: A rhetorical strategy in which a person continues to repeat something as true over and over again, even after it has been shown to be false. Some radio commentators are particularly prone to doing this: “Sandra Fluke wants the taxpayers to pay for contraception. She argues that it is the responsibility of the taxpayer to pay for her contraception. Sandra Fluke believes that contraception should be paid for by the taxpayer.”

Argument from Scripture: An argument which states that if some element in a source being cited is true, then the entire source must be true. This fallacy does not apply exclusively to holy texts or Biblical scriptures, though it is very often committed in religious arguments.

Begging the Question: Similar to the loaded question fallacy, this is an argument in which some argument assumes its own premise. Formally, it is an argument in which the conclusion which the argument claims to demonstrate is part of the premise of the argument. “We know that God exists because we see in nature examples of God’s design.” The premise of this argument assumes that nature is designed by God, which is the conclusion that the argument claims to support.

Circular Argument: This argumentative tactic is related to begging the question, but slightly different in that it uses one argument to claim to prove another, then uses the truth of the second argument to support the first. A lot of folks consider circular reasoning to be the same thing as begging the question, but they are slightly different in that the fallacy of begging the question contains the conclusion of an argument as one of its premises, whereas circular reasoning uses argument A to prove argument B, and then, having proven argument B to be true, uses argument B to prove argument A.

Appeal to Emotion, Force, or Threat: An argumentative tactic in which, rather than supplying evidence to show that an argument is correct, the person making the argument attempts to manipulate the audience’s emotions (“You must find Bob guilty of this murder. If you do not find him guilty, then you will set a dangerous murderer free to prey on your children”).

False Attribution: An argument in which a person attempts to make a position sound more credible either by attributing it to a well-known or respected source, or using a well-known and respected source’s comments out of context so as to create a false impression that that source supports the argument. As Abraham Lincoln said, more than 90% of the quotes used to support arguments on the Internet can’t be trusted!

Association Fallacy: A generalized form of the fallacy of guilt by association, an association fallacy is any argument that makes any assertion that some irrelevant similarity between two things demonstrates that those two things are related. “Bob is good at crossword puzzles. Bob also likes puns. Therefore, we can expect that Jane, who is also good at crossword puzzles, must like puns too.” Because our brains are efficient at categorizing things into groups, we are often prone to believing that categorizations are valid even when they are not.

Vividness Fallacy: Also called the “fallacy of misleading vividness,” this is the tendency to believe that especially vivid, dramatic, or exceptional events are more relevant or more statistically common than they actually are, and to pay special attention or attach special weight to such vivid, dramatic events when evaluating arguments. A common rhetorical strategy is to use vivid examples to create the impression that something is commonplace when it is not: “In New Jersey, a Viet Nam veteran was assaulted in a bar. In Vermont, an Iraqi vet was mugged at knifepoint. American citizens hate veterans!” It is effective because of a cognitive bias called the “availability heuristic,” which causes us to misjudge the statistical importance of an event if we can think of examples of that event.

Entrenchment effect: Also called the “backfire effect,” this is a tendency of people who, when presented with evidence that disproves something they think is true, will often tend to form a greater attachment to the idea that it must be true. I’ve written an essay about framing and entrenchment here.

Sunk Cost Fallacy: An error in reasoning or argument which holds that if a certain investment has been made in some course of action, then the proper thing to do is continue on that course of action so as not to waste that investment, even in the face of evidence that shows that course of action to be unlikely to succeed. In rhetoric, people will often make arguments to support a tenuous position on the basis of sunk cost rather than on the merits of the position; “We should continue to invest in this weapons project even though the engineers say it is unlikely to work because we have already spent billions of dollars on it, and you don’t want that money to be wasted, do you?” These arguments often succeed because people form emotional attachments to a position in which they feel they have made some investment that is completely detached from the value of the position itself.

Appeal to Authority: Also known as the argument from authority, this is an argument that claims that something must be true on the basis that a person who is generally respected or revered says it is true, rather than on the strength of the arguments supporting that thing. As social animals, we tend to give disproportionate weight to arguments which come from sources we like, respect, or admire.

Black Swan Effect: Also called the black swan fallacy, this is the tendency to discount or discredit information or evidence which falls outside a person’s particular range of experience or knowledge. It can take the form of “I have never seen an example of X; therefore, X does not exist;” or it can take a more subtle form (called the “confirmation fallacy”) in which a statement is held to be true because no counterexamples have been demonstrated (“I believe that black swans do not exist. Here is a swan. It is white. Here is another swan. It is also white. I have examined millions of swans, and they have all been white; with all these examples that support the idea that black swans do not exist, it must be a very reliable statement!”).

Confirmation Bias: The tendency to notice, remember, and/or give particular weight to things that fit our pre-existing beliefs; and to not notice, not remember, and/or not give weight to anything that contradicts our pre-existing beliefs. The more strongly we believe something, the more we notice and the more clearly we remember things which support that belief, and the less we notice things which contradict that belief. This is one of the most powerful of all cognitive biases.

Attention Bias: A cognitive bias in which we tend to pay particular attention to things which have some sort of emotional or cognitive resonance, and to ignore data which are relevant but which don’t have that resonance. For example, people may make decisions based on information which causes them to feel fear but ignore information that does not provoke an emotional response; a person who believes “Muslims are terrorists” may become hyperaware of perceived threatening behavior from someone he knows to be Muslim, especially when that perception reinforces his belief that Muslims are terrorists, and ignore evidence which indicates that that person is not a threat.

Choice Supportive Bias: The tendency, when remembering a choice or explaining why one has made a choice, to believe that the choice is better than actually was, or to believe that other options are worse than they actually were. For example, when choosing one of two job offers, a person may describe the job she chose as being clearly superior to the job she did not accept, even when both job offers were essentially identical.

Expectation Bias: Also sometimes called “experimenter’s bias,” this is the tendency of people to put greater trust or credence in experimental results which confirm their expectations than in results which don’t match the expectations. It also shows in the tendency of people to accept without question evidence which is offered up that tends to support their ideas, but to question, challenge, doubt, or dismiss evidence which contradicts their beliefs or expectations.

Pareidolia: The tendency to see patterns, such as faces or words, in random stimuli. Examples include people who claim to see the face of Jesus in a piece of toast, or who hear Satanic messages in music albums that are played backwards.

Rhyming Effect: The tendency of people to find statements more credible if they rhyme than if they don’t. Yes, this is a real, demonstrated cognitive bias. “If the glove don’t fit, you must acquit!”

Framing effect: The tendency to evaluate evidence or to make choices differently depending on how it is framed. I’ve written an essay about framing and entrenchment here.

Ambiguity Effect: The tendency of people to choose a course of action in which they know the exact probability of a positive outcome over a course of action in which the exact probability is not known, even if the probability of a positive outcome is generally somewhere around the same, or if the possible positive outcome is better. There’s an interactive demonstration of this effect here.

Fortunetelling: The tendency to make predictions about the outcome of a choice, and then assume that the prediction is true, and use the prediction as a premise in arguments to support that choice.

A-Lógica-do-Cisne-Negro-o-impacto-do-altamente-improvável-_Nassim-Nicholas-Taleb